Oxford is well known for its exceptional copyright Library – the Bodleian. But some of the better kept secrets of the university are the individual college libraries, often the first port of call for fresher undergraduates, and the preferred final resting place of finalists. Owing to the antiquity of many of the colleges, many of these libraries contain hidden, ancient bibliographic secrets. This week, I was lucky enough to lay my hands on one such secret – a first edition of Robert Hooke’s Micrographia.

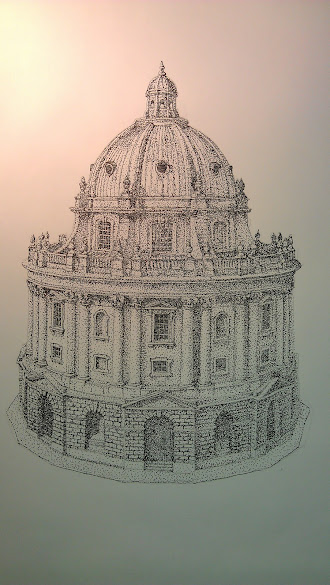

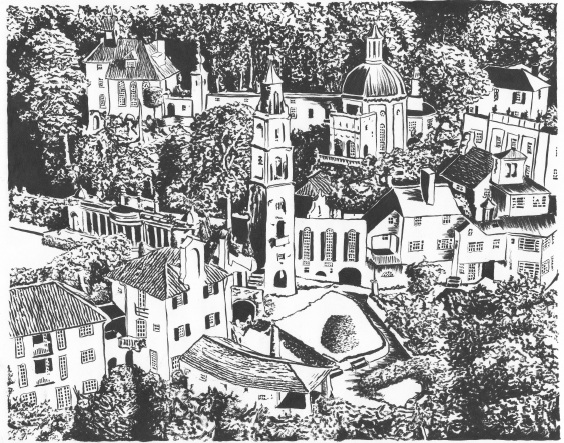

St Edmund Hall, dating back to the 13th Century, houses one of the first private college libraries in a small room above the chapel. The construction of the old library (the new library occupies a Norman church in the grounds) was completed in 1685, and was used to hold the collection amassed by the then Principal, Dr Thomas Tullie. It is a small and unassuming room, with enclosed bookcases lining the four walls of the main floor and an upper gallery. Small windows with heavy yellow velvet curtains allowed the spring light to fill the room. The collection is large and varied. Among the many eclesiastical tomes are books on natural history, travel in the Empire, even an instructional guide to Witches. Some books are chained. But of greatest interest to our little group of palaeontologists, was a rare first edition folio of Robert Hooke’s study of tiny objects through the microscope – ‘Micrographia: or, Some physiological descriptions of minute bodies made by magnifying glasses’. Handling the book with white cotton gloves and weighted ‘snakes’ to hold down the pages, it was a magical experience, and one that I hope I can share with a few photographs, courtesy of my colleague Jack Matthews.

Robert Hooke's Micrographia, first edition

Micrographia was the first published book of the newly established Royal Society (founded just around the corner at Wadham College), appearing in 1665. Robert Hooke, who studied at Wadham, developed his own compound microscopes with which to study microscopic objects, and he figured them in Micrographia as exquisite copperplate engravings, some as large fold-outs. Micrographia is best known for studies of biological objects, and it was here that the word ‘cell’ was first used to describe living biological units, alongside intricate drawings of cork. Pollen grains, seeds, and many insects are figured, and the large illustration of a flea has become and iconic image for science in this golden age.

Flea illustration from Hooke's Micrographia

But Hooke was a true polymath. His work strayed well outside the biological. Just like everyone does when given a microscope and some free time, he put everything he could find under there. Textiles, the point of a needle, the edge of a blade, a lump of oolitic limestone, hair (complete with hair louse). It is a wonder he didn’t draw his own fingernails, only it was probably too gross. And his drawings weren’t just limited to things he saw down the microscope. He included schematics of the microscope itself, light refraction and reflection in different systems, as well as a view of craters of the moon along with discussion of whether they were caused by impacts, or by volcanoes. He came to the conclusion that they were volcanoes, but we can forgive him just this time.

The book itself is beautiful. You can pick up a recent printing of it for barely anything these days, but there is something special about this fragile first edition. Leather bound, with cord binding, and marks to show it had once been chained, the pages gently discoloured, with mysterious bequeathements and catalogue numbers handrwitten – testament to its arrival in the very earliest days of the Library.

- Record of Hooke’s Micrographia in the catalogue of St Edmund Hall’s Old Library

The library had many more secrets to give up – including a second edition print of Newton’s Principia, and an early geological and palaeontological tome by Corpus Christi geologist Dr William Buckland.

Illustration of a Crinoid fossil by William Buckland

It is wonderful to know that these treasures are there to be found on our own doorstep, and are being preserved just as they always have been. Long may their presence be preserve to the deep scientific legacy of the University as a seat of learning.

Many thanks to Jack Matthews for the photographs, and to Vicky and Blanca for showing us the collections. Martin Brasier, Alex Liu, Linhao Fang, Jack Matthews and Jonny Baker-Brian shared the magical experience.

Yours truly with Micrographia in the Old Library, St Edmund Hall